This is a sample article from the April 2011 issue of EEnergy Informer.

Clever niche players have finally found a way to make money by encouraging consumers to use less.

Everyone must have heard the old adage, the cheapest kWh is the one you don’t use. In the age of high and rising — not falling — marginal energy costs, a kWh saved or not consumed is generally a good bargain. Replace an old incandescent light bulb with a compact fluorescent light (CFL) and you get the same amount of lumens using a quarter of the energy. Replace the CFL with an even more efficient and directional light emitting diode (LED), and you save even more over time — despite the higher up-front cost of the more efficient LEDs.

Consumers are slowly but surely getting the message — but it is still an uphill battle since so much of our capital stock is old and inefficient and nobody replaces a perfectly functioning refrigerator, furnace, motor or light bulb until and unless it breaks down. And some of these devices, refrigerators in particular — never break down.

Now, a new breed of companies have emerged whose business model is essentially to pay consumers not to use energy, especially when it is expensive to generate and deliver — such as during peak demand hours. The initial focus of these enterprises is on big energy users, large commercial and industrial (C&I) customers. But some are now going after smallish loads, including residential consumers, who can be aggregated into decent blocks of load, say an entire community, subdivision or apartment block.

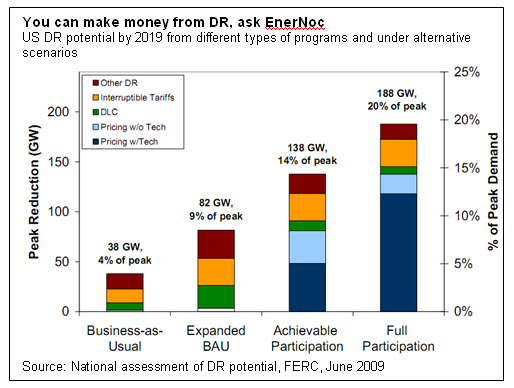

EnerNoc Inc. and Comverge Inc. have emerged as big names in the negawatt business, but there are a number of others trying similar schemes — essentially paying consumers who agree to cut back consumption when called to do so. The reward is generally geared to the value of the energy and/or capacity that can be aggregated and sold back to a grid operator in a wholesale market or to a distribution company who is short of energy and/or capacity.

The US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has been vocally supportive of the logic behind these demand response (DR) schemes, although how much consumers should be compensated for agreeing to participate is still being debated. As previously reported in this newsletter (“How much should we pay for DR?” Nov 2010), some economists believe that consumers who cut back consumption are already rewarded for electricity not used — and that should provide sufficient incentives for them to participate in DR programs.

This argument makes more sense when consumers are billed under dynamic pricing, where prices are cost-reflective in real time. Cutting back during peak demand periods would be highly advantageous since consumers would avoid paying for expensive electricity. Others believe that consumers should be paid above and beyond what they already save when they agree to participate in DR programs. A decision on this issue from FERC is expected in the near future.